HABITAT COMENSALISTA#INEDITOS2021 LA CASA ENCENDIDA OF MADRID

#INEDITOS2021 LA CASA ENCENDIDA OF MADRID

“Wisdom never says one thing and nature says another.”

(Decimus Junius Juvenalis)For many years we have been talking about ecology and sustainability as an urgent necessity for the planet and for humanity. But beyond economic or social measures, I believe that the only way to live in perfect harmony with this planet is through a truthful connection with nature. Knowledge is the only way to respect and understand the great source of wisdom that nature can offer us. Unfortunately, this is not so easy. The words of the Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han in his book "Loa to the Earth" are a clear example of how, little by little and unconsciously, man has separated himself from nature to the point of not feeling the painful price of its absence. We live apart from it, denying its rhythms and processes within us.

"For the first time in my life I dug into the ground. I dug deep into the earth with the shovel. The grey, sandy earth that came up was strange, almost eerie. As I dug, I came across many roots, but I could not identify them with any nearby plant or tree. So there was a mysterious life down there of which I had been unaware".

[...]

[The earth] is magic, enigma and mystery. If it is treated as a source of resources to be exploited, it has already been destroyed.

[...]

Today we have lost all sensitivity to the Earth. We no longer know what it is. We think of it only as a source of resources to be treated, at best, sustainably. Treating it with care means giving it back its essence.

*Han, Byung-Chul (2019). Loa a la tierra, un viaje al jardín. Herder Editorial

Such lucid observations, made by philosophers, scientists and artists, give voice to a cry that is not always made visible by the media, which get lost in more prosaic and less existential issues. In 2000, the scientist Paul Crutzen (1933-2021), winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, first proposed the term Anthropocene: a new geological epoch characterised by man's capacity to exert a significant and global impact on ecosystems. Never in history have human activities been so powerful in transforming and altering nature. This new concept not only took everyone by surprise, but also provided the diagnosis needed to start a debate and take urgent action on global warming and biodiversity loss.

There is no doubt that we must continue working to create sustainable companies, processes and products, but none of this will reach the citizen if we do not work on the link that every human being must establish with nature; Our actions start from our internal experiences. This is the key. So there will be no real change without this inner transformation. And art can help us a lot on this path.

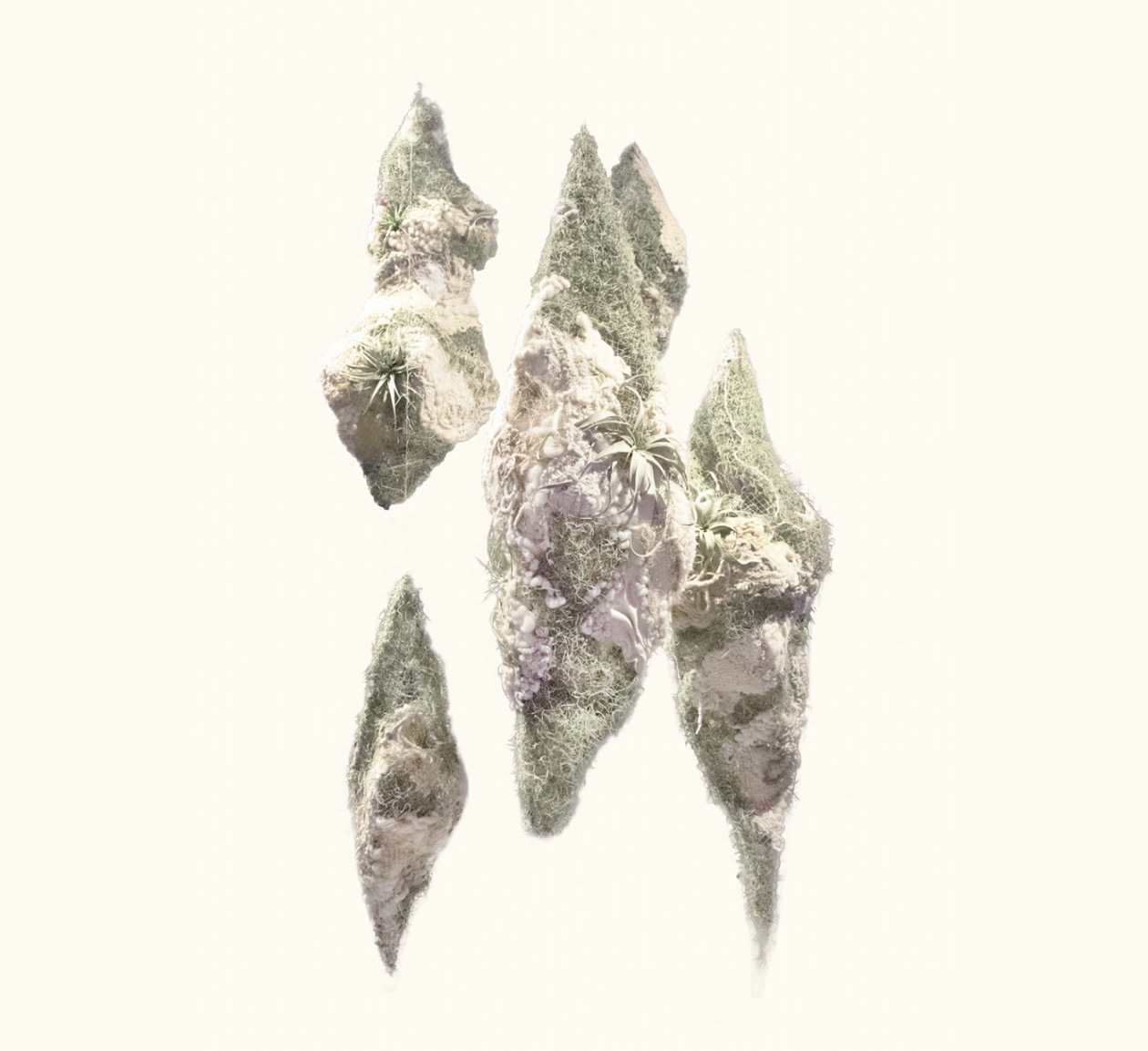

From these values and observations, Hábitat comensalista was born, a floating installation that seeks to raise awareness of the above by creating a designed and living habitat that is an example of this encounter between man and nature.

Among other things, commensalism is a form of biological interaction studied in science, in which one species benefits from the other without harming it. Tillandsias are a clear example of commensal nature. It is amazing to discover that there are thousands of examples of how the animal and plant worlds relate, coexist and help each other: biological interactions established between organisms that not only demonstrate the correct functioning and cooperation between them, but also serve as an example of the balance that we humans so desperately need.